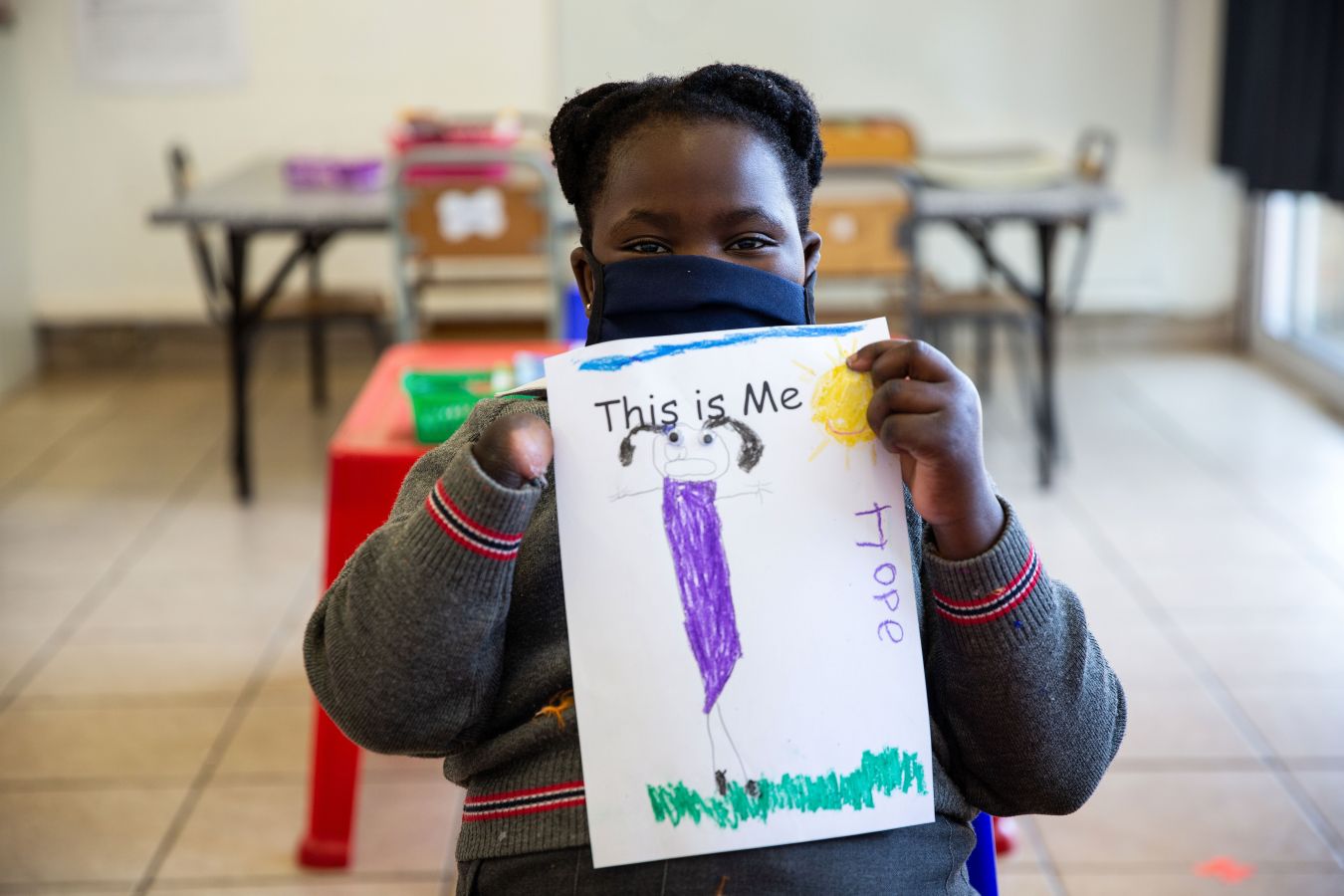

“For good mental health people need a (safe) place to go”. The mental health challenges of Somali and Congolese refugees in Johannesburg, South Africa

Media

Image

Media description

Photo credit: James Oatway. Used with permissionBlog content

The statement in the title of this piece was made by a social worker supporting cross-border migrants living in Johannesburg, South Africa. Responding to a question about what an “ideal” public healthcare system in South Africa should look like, the social worker suggested a three-pronged approach in which the first step would be “based on recognition that for good mental health people need a safe place to go.” While this assertion connecting good mental health with a sense of safety may seem obvious, it also points to a fundamental truth: that being safe or having a sense of safety lies beyond the reach of many.

This piece brings together a focus on a lack of safe spaces and the mental health responses to precarious urban migrants, asylum seekers and refugees in Johannesburg. Showing how unmet basic needs centre around the need for “a (safe) place to go" we suggest that they compound mental health challenges and create new forms of trauma. However, these are not be the extreme cases of mental ill-health and trauma that are often described as impacting forced migrants including self-harm, suicidal ideations, or violent outbursts. Rather, they are the extreme cases that have become routine - normalised, systematic, embedded: experienced by many and denied by some - anticipated and inevitable.

Migrants and city life

In Johannesburg, a city that has long been seen as an attractive destination to migrants from across the Southern African region and more widely, safety is not only out of reach but routinely denied to many. The majority of asylum seekers, refugees and undocumented migrants find themselves living in densely populated urban areas of Johannesburg; these diverse and vibrant spaces are also considered peripheral to the life of the city due to socio-economic desperation, high levels of violence as well as poor health and social welfare provision. While this impacts citizens and non-citizens, the high levels of exclusion, discrimination and xenophobia mean that forced migrants face heightened vulnerabilities, impacting their wellbeing and mental health. This has been increased by the catastrophic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic through which already vulnerable populations have disproportionately suffered and further separated from sources of help and care.

The mental health experiences faced by Somalian and Congolese migrants shaped our inquiry into how these challenges are endured and responded to in a context where ‘daily stressors’ – such as paying rent, finding employment, feeding children – not only compound traumatic stress but are a form of trauma themselves. This is part of the GCRF Protracted Displacement project, a broader study led by the University of Edinburgh, and in partnership with The African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS). Conducting a series of interviews with professionals working across the state and non-state healthcare sector, organisations supporting migrants and with migrants themselves in Johannesburg we consider how to better understand and respond to mental health challenges while working with everyday realities.

The crisis of mental health in South Africa

It’s just the total lack out there of actual services available, whether you’re a South African or not. You know the whole mental health scene in South Africa is just a disaster, so I think you need to bear that in mind as well when trying to look at services available for migrants is that there’s just a total lack of services generally (Professional nurse, Johannesburg).

Mental health in South Africa is in crisis - both in terms of the increasing numbers of those experiencing poor mental health and of the failures of the public health care system to adequately respond to mental health care needs. Although South Africa has taken some critical steps in prioritising mental health through legislation and policy reform, it has failed to implement a rights-based approach to deinstitutionalise care and also to engage with the social determinants of mental health and wellbeing in the country – as the South African Human Rights Commission concluded, “Mental health services are in a state of chronic and systemic neglect, coupled with mismanagement and a dire lack of resources.”

Low prioritisation of mental health and of under-funding is common across many countries, particularly those in the global South. Yet the picture for asylum seekers and refugees in South Africa needs to be understood through the lens of intersecting vulnerabilities; as a migrant, as a foreigner, as someone without documents, as someone who is poor, a caregiver, a mother, as someone with mental health challenges. These frames of vulnerability and othering, compound one another and amplify experiences of trauma.

Trauma: unsafe spaces and unmet needs

When they [asylum seekers] leave…they are not leaving into a safe space, they are leaving and moving into a very dangerous, threatening, inhospitable and hostile place (Psychologist JHB)

The idea of ongoing fear and trauma is exacerbated by the challenges of accessing mental health care and also by the failure of the mental health to respond to the lived experiences of trauma. Our understanding of trauma here, while the subject of multiple medical, social and political diagnosis and debate, is guided by the key informants we spoke to. Many described trauma as a form of rupture - a rip or tear in the fragile skin of survival needed to make a life in Johannesburg. Survival defined by the everyday effort of getting up, looking for work, getting children to school, finding money to cook meals, asking for help, dealing with rejection; survival that is precariously knitted together and then so-easily ripped apart time and time again.

This idea of trauma as rupture shatters the common assumption shaping therapeutic responses to trauma that there can be a way to process and make meaning in a safe environment; that bad things sometimes happen to good people and so there can be ways to be held and return or remake life. Instead, in this context, bad things happen to good people all the time. We therefore cannot assume there is a clear way forward especially where there are few, if any, safe spaces.

Basic needs can provide a sense of safety: securing employment for example, can provide an income and much-needed routine, familiarity and the ability to pay school fees and buy medication when sick. The ability to meet basic needs was described by key informants as connected directly to a sense of identity, dignity, belonging and - critically here - safety. In the same way that Miller and Rasmussen argue that daily stressors – in the form of poverty, social isolation and poor housing - erode people’s coping resources and mental health, the inability to meet basic needs not only compounds a layered, continuous trauma which becomes a form of trauma itself.

Responding to mental health in context: a safe place to go

While our research in Johannesburg highlights the many challenges faced by forced migrants in accessing help for mental health it has also raised questions about responses. While participants were aware that they could not fix the deeply embedded structural and systematic weaknesses of the public mental health system any time soon, they also recognised the importance of fixing a response; a response that focuses on immediate context and crisis and “a safe place to go” with the hope of longer-term consequences.

This approach also opens up space to see trauma as ‘ongoing-lived-experience’; as ongoing rupture in which loss, marginalisation, vulnerability as well as agency and survival entangle. Basic needs here are central as they not only confirm a way to keep going but for some confirm an existence – a recognition of being here and belonging through the safety and security of knowing where you are sleeping, that you have food for your family, a cup of tea made for you as a sign of care and that when you need support – including for health – that you will be listened to and heard. As we state at the start: these are the extreme cases that have become routine - normalised, systematic, embedded: experienced by many and denied by some - anticipated and inevitable.

It is these issues that our research suggests is the reality that needs to be focused on in discussions about responding to the mental health of forced migrants. Basic needs must be met as a part of a more complex and wider mental healthcare response and critically forced migrants need to feel they have “a safe place to go.”

Dr Rebecca Walker is a research associate with The African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS) at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. With a background in social anthropology, Rebecca has worked broadly on issues related to gender, migration, and health using an intersectional lens. Her work as a postdoctoral fellow and then research fellow has focused on access to healthcare, experiences of xenophobia and violence, migrant sex work and human trafficking and, the survival strategies of asylum-seeker and refugee women in South Africa.

Jo Vearey is an Associate Professor and the Director of ACMS and holds an Honorary Fellowship with the School of Social and Political Science at the University of Edinburgh, and a Senior Fellowship at the Centre for Peace, Development and Democracy at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. Jo has a background in public health and her interdisciplinary research focuses on the intersections between migration and health.

Dr Tackson Makandwa and Dr Dostin Lakika are postdoctoral research fellows at the ACMS. Tackson's research looks at the intersections between migration, maternal health, and wellbeing. Dostin's areas of research include migration and displacement, former soldiers, violence and memory, migration and food consumption, (mental) health, and illness.

Through ACMS Rebecca, Jo, Tackson and Dostin are a part of the GCRF Protracted Displacement project with the University of Edinburgh. This multi-sited project (across Kenya, Somalia, South Africa and Eastern DRC) aims to help Somali and Congolese displaced people to access appropriate healthcare for chronic mental health conditions associated with protracted displacement, conflict, and sexual and gender-based violence.